October 16, 2009

George Tuska, 1916-2009

George Tuska, 1916-2009

George Tuska

George Tuska, a comic book artist who was one of the few of his peers to have measurable success in both the the initial 1930s-1940s flood of comic book production and during their revival as more of a specialty publishing form in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, passed away near the stroke of midnight between October 15 and October 16.

Tuska was born in Hartford, Connecticut in 1916. His parents were Russian immigrants who met in America. Tuska's father died when the future comic book artist was a teen, and his mother worked two shifts as a cook in a restaurant she established on her own. It was as a child that Tuska suffered the fever that initially damaged his hearing.

Like many future comic book artists, Tuska saw more general training as an artist before moving into that field. His lambiek.net entry has him finishing studies at the National Academy School Of Art in 1937, while an initial obituary asserts he may have attended classes the National Academy of Design as late as 1939; I would favor the latter. In

an interview from 2001 conducted by PC Hamerlinck, Tuska describes his move into art thusly:

After high school I visited my aunt in New York City, where I ended up working a few odd jobs. One was designing women's costume jewelry. It was fun, but I soon found out that it just wasn't my thing. Shortly thereafter, a friend of mine invited me to work out with him, lifting weights at a local gym. I exercised for five hours that day. The next day I was so sore I couldn't get out of bed. My friend came over, and we dropped in to visit a friend of his who was a sculptor. His studio was on one of the West 70s Streets, overlooking Central Park. I never got to know his name, but he knew I was interested in art, so he recommended me to the National Academy of Design. At the time it was located at 104th Street and Amsterdam Avenue. Thus began my art career!"

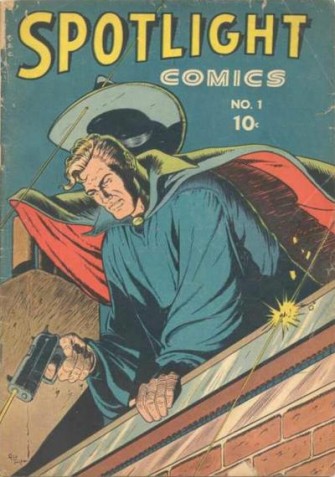

Better documented than the length and location of his schooling is that Tuska began his comics career during the industry's initial burst of publishing activity, joining the Eisner/Iger studio and working as an assistant on the newspaper strip

Scorchy Smith in roughly the same time period. For Eisner/Iger he worked on the titles

Jungle,

Mystery Men,

Planet Wonderworld and

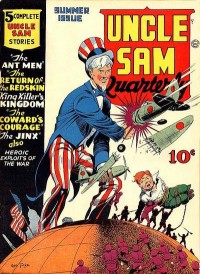

Wings. He joined the Harry "A" Chesler Studio for a while, where he contributed work to features such as

Captain Marvel,

Golden Arrow and

Uncle Sam. He would later work for Eisner after his separation from Iger. Other publishers for whom Tuska worked in this initial period included Quality Comics -- for whom he created the character "Hercule" -- Fiction House, Harvey, Fox and Standard.

Tuska was drafted into military service during what looks like the latter phase of World War II. Although comics artists of that period didn't always find a deployment that took advantage of those skills, Tuska served his country at South Carolilna's Fort Jackson as an artist. He drew military plans, and found time to provide illustrations to army magazines.

Tuska returned to comics after the war, and enjoyed his first major success as a reliable performer on a variety of features in the best-selling

Crime Does Not Pay title, splitting time between that work and on solid adventure titles of the period such as

Black Terror and

Doc Savage. He also did his first sustained work for Marvel, turning in pencil work on a variety of gigs into the early 1950s.

Tuska was one of many comics artists to see his workload in comic books decrease due to circulation and censorship issues in the 1950s. He found work in comic strips. Tuska returned to the adventure strip

Scorchy Smith as its primary artist from 1954 to 1959. He then took over on both dailies and Sundays with

Buck Rogers, a job he kept well until the 1960s (he dropped the Sundays a couple of years after the dailies, in 1967).

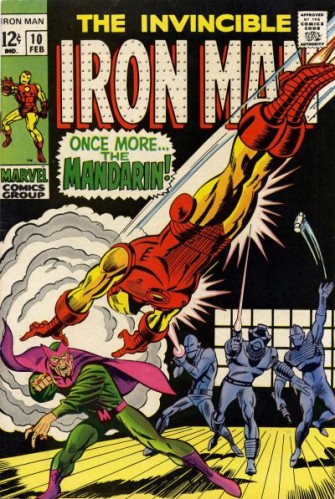

A drop in the popularity of adventure strips and a more stable market than that which existed in the previous decade began to entice the veteran illustrator back into the comic book fold. Although his re-entry into comic books came through Tower Comics, perhaps the most famous entity that tried to capitalize on the success of new superhero books at DC and Marvel, he is best known for his work at Marvel during this period. One early assignment that grew in stature over the years was inking Jack Kirby on the Captain America "Sleeper" storyline that appeared over several issues of

Tales Of Suspense. He worked fill-in slots on various titles, before setting in on the Iron Man character for a decade-long run. Tuska also found work with the Luke Cage character, as well as performing duties on

Ghost Rider,

X-Men and

Daredevil.

Earlier this year, the AV Club

examined his work during this time period for the article "Reinventing The Pencil," and singled him out as the embodiment of a certain kind of uninspired craftwork:

"It's hard to find anyone who would say a bad word against [Tuska] as a man. But as an artist, his Silver Age work for Marvel Comics... Well, it wasn't exactly bad; Tuska was perfectly competent, and his art for titles like Iron Man and The Incredible Hulk is decent, though unspectacular. But his drawing was so quickly assayed, and so essentially flavorless, that he became the King Of The Fill-In Issue, hopping in to provide bland, forgettable work whenever someone else blew a deadline. He thus played an inadvertent part in setting up the Big Two's creed of speed over quality, and helped establish the Marvel house style, which nurtured some young artists, but acted as an artistic straitjacket for others."

Another way to look at Tuska's work during this period was that he did so many fill-in comics because the expansion in the Marvel line put a significant strain on the available talent pool; a versatile artist who could produce professional work on short notice must have been a huge boon to that company's bottom line. It's unclear if Tuska suffered a bit in terms of overall ease making the transition from strips back into comic books, and whether he felt entirely comfortable working under the basic model established by Jack Kirby: his layouts were certainly more imaginative than the standard at the time, and the way in which characters like Luke Cage held a lot of their strength in their shoulders and punched from their legs up through their torsos betrayed his knowledge of strength and fitness. His signature flourish may have been characters in arrested motion, coiled in preparation for violence like so many pulp heroes of an earlier generation, legs splayed in the form of a near-base ready for what might come next. While perhaps slightly diminished in otherworldly power that many comics artists milked from the contrast of stillness and exaggerated movement, Tuska's heroes almost certainly suffered fewer muscle pulls.

In the 1970s, Tuska took one last journey into the world of newspaper strips, becoming the artist on the

World's Greatest Superheroes effort featuring DC Comics heroes. He also worked for that company's comic book line on various titles in much the same plug and play manner in which -- save for Iron Man -- he was employed by Marvel.

Tuska retired from comics in the middle 1980s, but remained active in commissions up until several weeks preceding his passing. As more and more attention began to be paid to the comic book artists of the past through the development of magazine sources, Tuska received attention as a physically impressive memorable presence to many in that first generation of comic book artist. Dewey Cassell's book,

The Art Of George Tuska, was published by TwoMorrows in 2005, documenting various phases to his long career. A thinly disguised version of Tuska, a character called "Gar Tooth," appeared in Will Eisner's 1986 paean to the early days of comics,

The Dreamer. Like many personal reminiscences of Tuska, that portrayal was of someone physically imposing -- as noted above, Tuska began to lift weights at about the same time he entered into art -- but of a friendly, even gentle nature. He has recently been an Eisner Hall of Fame nominee.

One of the stranger and surprisingly telling tributes paid Tuska in recent years has been

the occasional Internet posting either including or outright centered around a panel from his short run on

Hero For Hire, where in that title's ninth issue Luke Cage brazenly asks Dr. Doom for monies owed with the line "Where's My Money, Honey?" While that issue may be best remembered for that oddball bit of street slang from Steve Englehart, the story itself turns on Tuska's ability to depict comic book violence in a way that blends fantasy and reality: namely, the character's decision to strike a specific point in the bad guy's armor until it's weakened and begins to malfunction. In that sequence, Luke Cage certainly came across as a man with the ability to punch his way into Marvel's upper tier of superheroes, and through his portrayal of a corrective, "what if?" situation that added to rather than subtracted from the general storyline of a still wobbly Marvel Universe, Tuska cemented his reputation as one of the more iconic superhero artists of that decade -- two full generations after entering comics.

George Tuska was 93 years old. He is survived by his beloved wife of over 60 years, Dorothy, their three children and a number of grandchildren and great-granchildren.

posted 8:30 am PST

posted 8:30 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives